A Story of Land, People, and Resilience in Western North Carolina

By Helen Headrick

In Western North Carolina, where ridgelines roll like waves and creeks cut through ancient valleys, the land speaks in quiet, powerful ways. For Jonathan Perry, a lawyer, hiker, and regional leader with Legal Aid of North Carolina, it’s always been a conversation worth listening to.

“I need the mountains,” Jonathan says plainly. “There’s something in me that needs them. Needs the quiet, the solitude, the strength. And there’s something in the people here that mirrors that terrain. They’re just as rugged. Just as resilient.”

Jonathan has spent most of his legal career in the western part of the state, living and working in places like Morganton, Sylva, and Boone. He currently manages Legal Aid of North Carolina’s offices across the far western counties, leading a team of attorneys who serve low-income residents facing serious legal challenges: housing, disaster recovery, and domestic violence. It’s work that often happens behind the scenes. But in the wake of Hurricane Helene, that changed.

“When Helene came through, it was unlike anything I’d ever seen,” Jonathan says. “The rivers didn’t just flood. They moved. I mean literally moved. We’re talking about maps being redrawn, about land that won’t ever be the same again.”

For a region already shaped by water and time, Helene brought a new kind of violence. Creeks surged into rivers, landslides shut down the Blue Ridge Parkway, and in some places, entire hillsides were swept away. Trails vanished, forests fell, and families found themselves cut off, sometimes for weeks, with no power, no roads, and no way to get help.

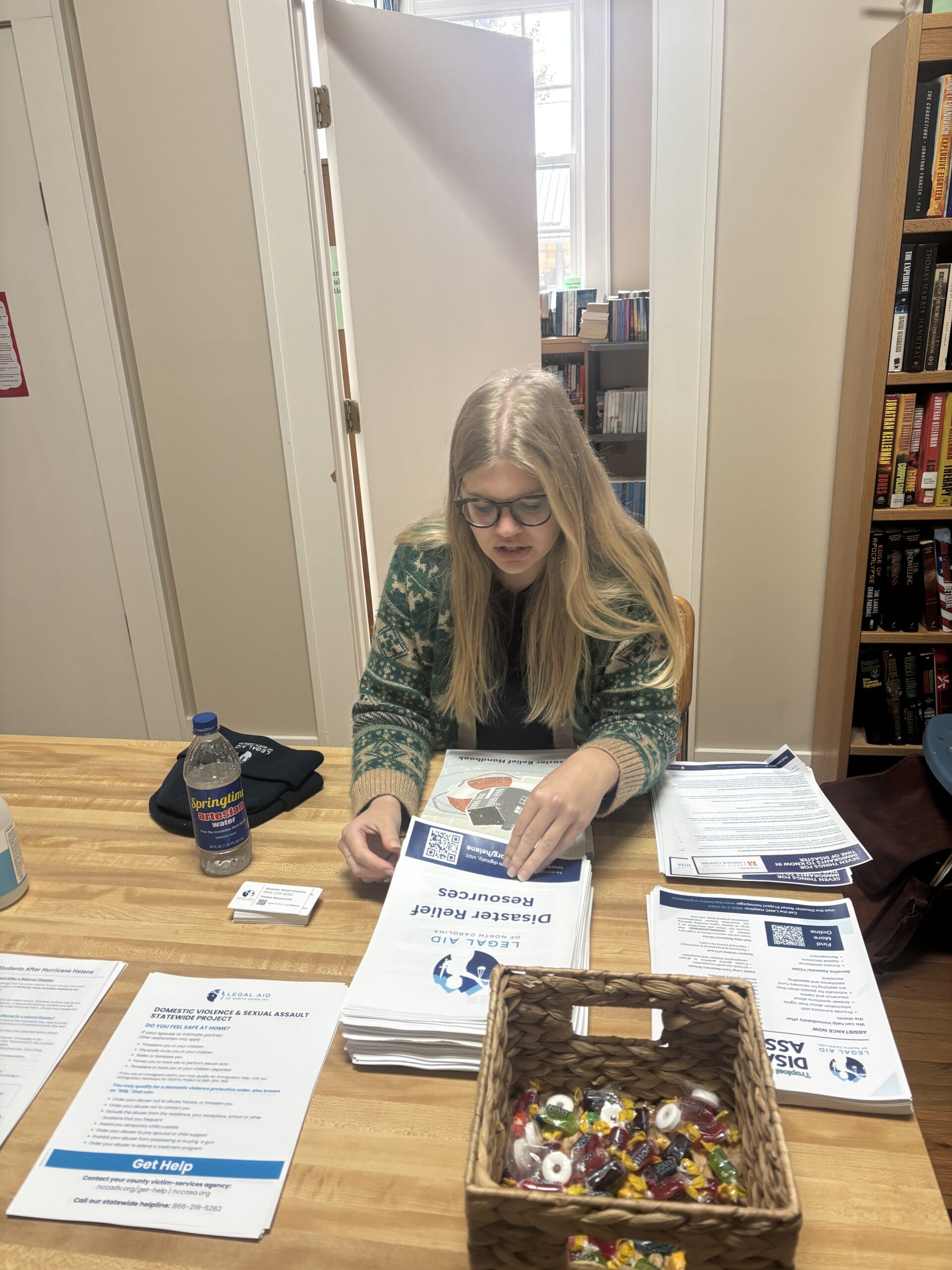

Jonathan saw it all up close. Legal Aid of North Carolina staff fanned out across counties, setting up in shelters and community centers, responding to calls, walk-ins, and urgent requests.

“The needs were immediate and overwhelming,” he says. “People had lost everything—possessions, homes, family members, neighbors, and IDs. We had folks showing up at Red Cross shelters who couldn’t prove who they were anymore. And without ID, you can’t apply for FEMA aid. You can’t get food stamps. You can’t rebuild your life.”

One case that stays with him is a man who lived in a tent near the French Broad River. “He lost everything in the flood—documents, clothes, his entire shelter. And the kicker was, without identification, he had no way to access support. That’s where we stepped in.”

Jonathan and his team helped hundreds of people find their footing. They replaced IDs, filled out aid applications, and simply showed up for those with no one else to turn to. But carrying that much loss takes its toll.

“There comes a point where you carry too many stories,” he says. “And when that happens, you have to find a place to set them down.”

For Jonathan, that place is the trail. He took time off, packed his gear, and headed into the woods. Into quiet. Into solitude. Into the kind of healing only the mountains can offer.

“When I hike, I’m not solving problems,” he says. “I’m just breathing. Moving forward, one step at a time.”

Jonathan’s connection to the Appalachian landscape goes beyond the scenery. For him, it’s deeply personal. He started hiking in college, spending spring breaks exploring mountain trails. Later, when he moved to Western North Carolina, it became part of his daily rhythm.

“There’s something called ‘forest bathing’ in Japanese culture,” he explains. “It’s the idea that just being in the forest lowers your stress. That’s absolutely true for me. When I’m out there, I’m not a lawyer, not a manager. I’m just Jonathan.”

His favorite spots? Max Patch, a bald on the Appalachian Trail in Madison County, where the mountains stretch in every direction. Joyce Kilmer Wilderness, home to towering old-growth poplars. “There’s magic in those places,” he says. “You feel small in the best way. You feel part of something ancient.”

Hiking isn’t just recreation for Jonathan. It’s how he handles the emotional weight of his job. “This work is hard,” he says. “You listen to trauma every day. People come to you after the worst thing that’s ever happened to them and ask for help. If you don’t have an outlet, it’ll eat you alive.”

That’s why he encourages his staff to find a restorative hobby, something just for them. “You need joy in your life,” he says. “Something you can pour yourself into that gives back in a healthy way. For me, that’s hiking.”

And after Helene, the trails gave him something else: perspective. “When you’re climbing 3,000 feet over four miles with a pack on your back, you’re reminded what effort feels like. You’re reminded that progress takes time. You can’t outpace the mountain. You have to go at its pace.”

What struck Jonathan most after Helene wasn’t just the damage. It was the grassroots brilliance of the community response.

“In places like Mitchell and Yancey counties, everything shut down—roads, water, power. But within a day, people mobilized,” he recalls. “The fire departments became command centers. Volunteers ran supply chains from the high school. Cadaver dogs worked the rivers. It was like a war room, but run by pastors’ wives and high school teachers. It was incredible.”

He remembers daily briefings—tight, no-nonsense meetings where everyone had three minutes to report. “No soapboxing. No politics. Just: ‘This is what we’re doing today. Who needs help?’ And it worked. Duke Energy said they were 30 days ahead of schedule because of the community effort. That’s resilience.”

But the real lesson wasn’t in logistics. It was in the spirit. “These were people who’d lost their homes, who were still scrubbing mold out of their basements, and they were showing up to volunteer for their neighbors. There’s a toughness here, a generosity, that’s hard to describe.”

He pauses, then adds, “But I’ve seen it before. In the trails. In the land. These mountains have survived colonization, deforestation, industrialization, and now climate disaster. They’re still standing. And so are the people.”

There’s a passage Jonathan often returns to from On the Spine of Time by Harry Middleton:

“There is something in me that needs mountains and fast mountain streams… There is no true wilderness here, but there is wildness, honest and deep and as much as a man could hope for. These mountains are sincere. They are a place of margins rather than pristine grandeur. There is as much ruin along these ridges, deep in these valleys, as there is natural glory. In these thick forests man and the land have collided again and again, battled for hundreds of years, and still there is no clear victor.”

That quote, Jonathan says, captures it perfectly. “We’re not here to conquer this place. We’re here to live with it. And when disaster hits, like Helene did, we see that the land and the people are inextricably connected. Both scarred. Both strong. Both still here.”

As tourism slowly returns and trails reopen, Jonathan continues to hike—sometimes alone, sometimes with his young daughter, sometimes just to feel like himself again. “Every time I reach a summit, I think: this land has been through hell and back. And it’s still beautiful.”

Western North Carolina is still recovering. But like its terrain, and the people who call it home, it’s not going anywhere.